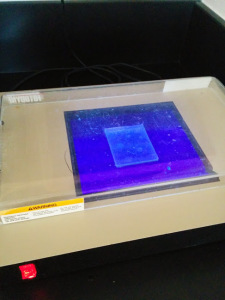

Our first attempt at PCR. The gel worked, as is evidenced by the ladder to the left, but our DNA did not work. There is a FAINT band in the third lane. Also yes, those are sloths, but they’re unrelated to this research.

So, for the non-science types, what the hell am I talking about? Last week, I extracted squirrel DNA from the liver of a deceased California Ground Squirrel. We used the Nanodrop machine to assess the purity and concentration of our samples.

Yesterday, I prepared and ran the first polymerase chain reaction (PCR). PCR is a process by which specific regions of DNA are amplified. Basically, we’re making a lot of copies of a certain part of the DNA. This is useful because this region of DNA usually has sequences that are repeated a different number of times, and this number of repeats is passed down from your parents. So you can look at the size of the fragments side by side with the putative parent and decide if they have similar sequences. We’ll hopefully analyze around 15 sequences, known as microsattelites, in order to determine parenthood of individual squirrels.

How do we look at the fragments? We use a process called gel electrophoresis, which separates macromolecules such as DNA, RNA, and proteins based on size using an electric current. DNA is a negatively charged molecule, so we load it in to the negatively charged side and the current causes it to move across the gel towards the positive charge.

First, we pour agarose gel in to the box and allow it to set.

This is the box used to run the gel electrophoresis. You can see the positive (red) and negative (black) ends.

Little wells are made in the gel while it sets, and once the gel is firm, we fill the box with buffer (to conduct the current) and load samples of DNA mixed with a dye in to each well. In one well we put a “ladder,” or a sample with fragments of known size. The ladder used above is a 100 base pair ladder, which means that each band is 100 base pairs. The brightest band is 500 bp, and they go down to 100 bp. The shorter fragments go down farther on the gel because they encounter less hinderance from the gel molecules, while the longer fragments move slower and will show bands towards the top of the gel. There is also often some sort of artifact, like the faint, diffuse band at the bottom of the ladder.

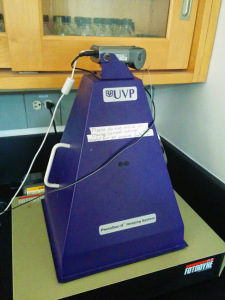

After running the gel for about 45 minutes, we can take it out and look at it under UV light, which makes the dye fluoresce. Then we take a picture of it and come up with the green thing shown at the top of the post. We even have a fancy camera set up and special photo printer.

Fancy/ghetto gel camera setup. It’s just a regular camera zip tied to that purple hollow pyramid thing.

That’s all there is to it. Except the gel we ran today showed no products from our PCR. So now I’m going to spend the weekend coming up with every single thing that could have possibly gone wrong, and how to fix each one. And then next week, I’ll try all my solutions and see if anything works. I’m also going to go back to the literature where we found our possible primer sequences and see if I can refine my protocol a bit.

So that’s it: Science, folks. It doesn’t work a lot of the time, which actually leaves us with more questions to answer than when we started. But we’ll get there, and it’s worth it. The setbacks almost make me more excited.